Discovering the Archeology that is Exhuming History at Williamsburg

This post may contain affiliate links where I earn a small commission when you make a purchase using the links at no additional cost to you.

During our week in Williamsburg, we stepped back into colonial times and watched as mysteries of the past became unearthed.

Williamsburg, VA

If you’ve ever wished for just one moment that you could travel through time then Williamsburg, Virginia may be your paradise. Sandwiched between Virginia Beach and Richmond, at the center of the Virginia Peninsula, is this town that bustles just as it would have in the 18th century. Colonial Williamsburg is the largest outdoor living history museum in the country. Horse drawn carriages replace motor vehicles along the cobblestone streets; In-character actors walk beside you in time period clothing; Open storefronts line the renowned Duke of Gloucester Street, giving visitors the opportunity to see how people made a living in Colonial Virginia.

During our weeklong stay in Williamsburg, Drew and I enjoyed walking these historic streets, particularly Duke of Gloucester because its dog friendly atmosphere meant Charlie could come along for the adventure. During the first week in November, the trees lining the historic district all showed us stunning shades of amber, pine and scarlet. We visited The Spice and Tea Exchange, meticulously smelling the contents of the glass jars which lined the walls of their shop before selecting two varieties of freshly steeped, exotic teas that we held close to our chests as we braved one particularly brisk autumn afternoon. The stroll down Colonial Williamsburg felt like a walk through time.

The colors of the trees were absolutely breathtaking during the first week in November. Paired with the colonial architecture, we never wanted to leave Duke of Gloucester Street.

For those of my friends who work up an appetite from their venture, Pierce’s Pitt Bar-B-Que can be found just a short drive from the colonial district. Worth every penny that you may spend on gas during the process, this casual establishment serves up slow smoked meats smothered in their signature, tangy barbeque sauce within a 70s inspired atmosphere. It’s classic. It’s delicious. It’s most definitely unmissable if you’re in the area. We went to Pierce’s Pitt twice during our week here because we simply couldn’t get enough of their Super Doc Sandwiches, prepared “All The Way” of course.

On our last day in town, we even squeaked in a trip to Busch Gardens Williamsburg which gave both Drew and I intense feelings of nostalgia as we remembered running through amusement parks as mischievous children who took every opportunity to escape the sight of their parents. Real quick, while I am on the topic, one thing I learned from this adventure is that if you are ever wondering when the best time to visit an amusement park sans the crowds, the weeks between their Halloween and Christmas themed events is an excellent contender! We all but had the park to ourselves on the weekend after Halloween, walking on every ride, only pausing to allow our inner ear to equalize before heading to our next thrill. While our imagination might forget that we are not still children, our stomachs never do.

Since we’re all science lovers here, I thought I would share that you can visit the parrot aviary for free while in Busch Gardens. Its fabulously overstimulating and just as fun as any roller coaster they have there.

Even with all of these other affairs giving it a run for its money, still, there is something far more exceptional taking place beneath the surface at Williamsburg - something that could provide us a clearer picture of what life was like before cameras were even invented. I’m talking about the many archeological digs that are happening across the 300 acres of Colonial Williamsburg soil. On a noble quest to answer questions about the area’s past, archeologists search for clues within the soil and piece together the puzzle of forgotten history. I visited three of these dig sites and spoke to the archeologists there about the science of archeology, the treasures they have dug up, and what implications they could have on the interpretation of history.

Williamsburg Excavation Sites

Custis Square - Named aptly for the owner of the 4-acre property during the 18th century, John Custis was a brilliant gardener, frugal business man, and first father-in-law to America’s earliest first-lady, Martha Washington. Colorful as his description may be, he has a persistent reputation for being cruel, often quarreling with his wife in public locations and profiting from the labor of over 200 enslaved people who worked on his tobacco plantation. He is not someone who history remembers with particular fondness, yet the land which held his estate is the site of one of the largest digs happening at Colonial Williamsburg.

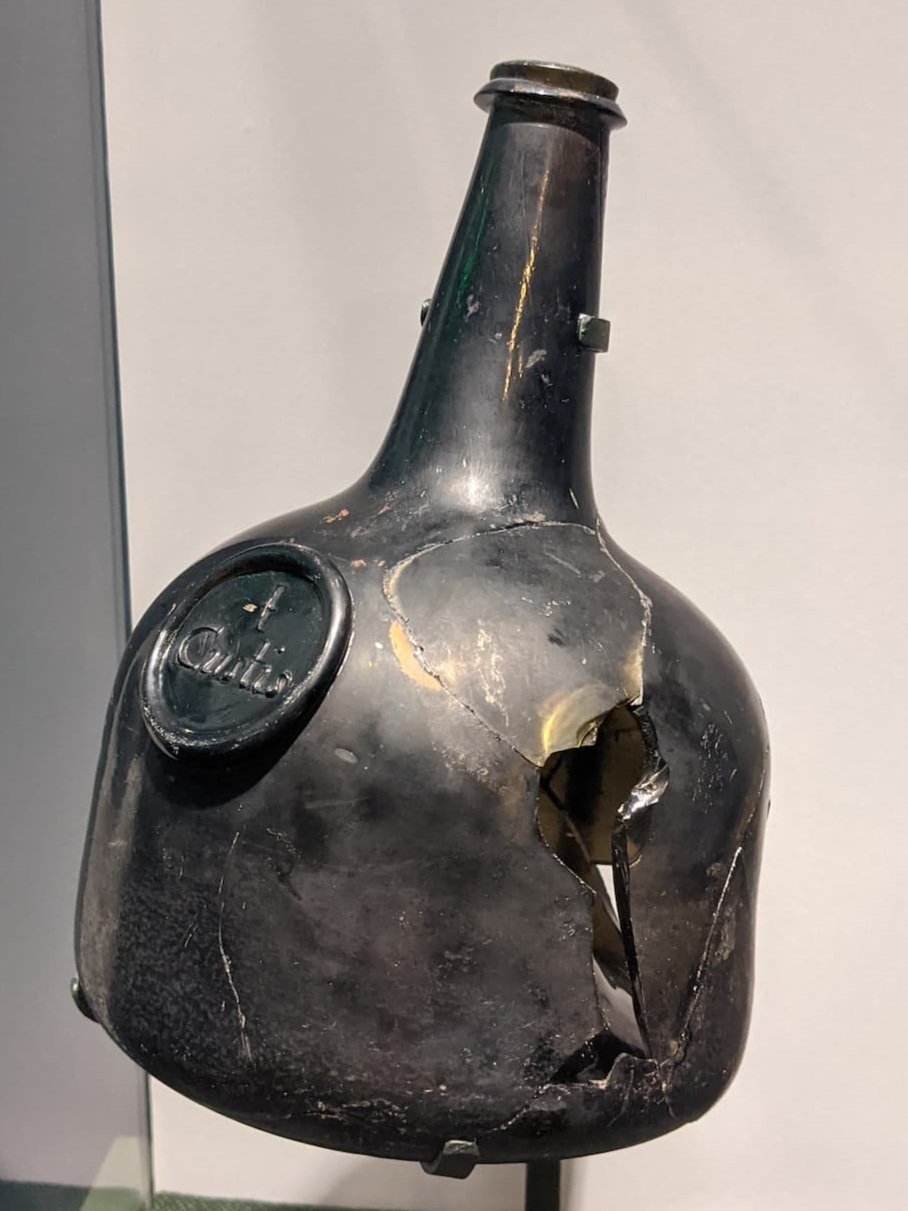

The interest here lies within the unique combination of Custis’s upper class status, his extraordinary garden, and his heavy involvement in slavery, providing archeologists a chance to learn about the dynamics of enslavement, consumerism, gardening practices, and the scientific thought process of the time. A unique feature of this site is an old well which went out of use during Custis’s time, leaving him to adopt the then common practice of using it as a makeshift dumpster. This well is now a treasure trove, the water at the bottom creating an anaerobic environment that slowed the decomposition of the items found there and allowed for the long term preservation of organic matter. The archaeologist working on the site pulled out a bag of peach pits as she told me about the all but magical well, smiling as she explained that many of them were probably eaten by Custis himself.

Perhaps more importantly, than any of this, though, is the fact that Custis did not work on his gardens by himself. In terms of our botanical and agricultural knowledge, we walk today at the end of a path of progress that was built by the help of those he had enslaved. As benefactors to that knowledge, we have the obligation to acknowledge the labor and sacrifice that allowed those bricks to be laid, a mission which would be impossible if we didn’t first strive to learn about their lives. Historical disregard for the human rights of enslaved Americans means much of this knowledge has been disposed of without care. While some of it may be gone forever, much of it can be found beneath our feet if we only gave the effort required to search for it.

The soft landing environment of Custis’s well allowed for the protection of fragile materials such as the glass which makes up this “salve pot” which was used to store wine.

First Baptist Church - The site of the original First Baptist Church of Nassau Street lies in downtown Colonial Williamsburg. Founded in 1776, it was one of the first African American congregations and was formed from both free and enslaved black worshippers. In 1856, a brick building on Nassau Street became the official worship center for the church, and would continue that way for the next 100 years. The excavation occurring now is the first on the site, already uncovering the foundation of the original structure that archaeologists believe may have first been used to host worship services here.

As no building remained standing at the site during the time of this excavation, the findings from this project will be indispensable in guiding reconstruction of the building while keeping with its original architectural integrity. It will also provide descendants, and current members of the congregation the chance to learn about aspects of their cultural worship practices that may have become buried with time.

It was recently announced that, throughout the excavation site, archeologists have begun to uncovered burial sites which they believe to be associated with the church. With the guidance of the church’s congregation, the archaeologists have continued their work while limiting any disturbances to the grave sites. They hope to identify the bodies with their findings and memorialize their grave sites with the respect the dead deserve, yet would never receive without these laborious excavations.

Here, archeologists work to carefully extract artifacts at the First Baptist Church site while leaving any located burials undisturbed.

Powder Magazine - The Magazine Site is unique in not just its appearance, an octagonal central building with pointed roofing surrounded by a seven foot tall, eight sided, brick wall, it also has a distinct story. On the surface, what would later be known as Powder Horn, Powder Magazine and Public Magazine was a storage depot used to safeguard weapons and gunpowder for the protection of the Virginia Colony. Exponentially more pivotal than that, though, is its involvement in one of the most influential moments in the path towards independence for the United States.

It was a Friday, April 2 of 1775 to be precise, when the man who was currently serving as the last royal governor to Virginia, John Murray, followed executive orders by dispatching a small army to the Powder Magazine in the early hours of the morning. The soldiers stole the vast majority of the colony’s gunpowder reserve, sparking anger and mistrust from the colonists towards Great Britain. It only took a year from this point for Virginia to sever its allegiance to Great Britain, becoming the first state to do so, and quickly motioning for the remaining 12 to follow suit.

Drew walks toward the Powder Magazine where the archeological excavation is happening within the outer octagonal wall.

We know quite well how this story ended, but it is a shame that so many details of this initial spark have been forgotten. Following a fire in the late 19th century, the Powder Magazine was rebuilt with little care in retaining its original architectural features. Artifacts, including cannon balls and other ammunition have been buried in the Magazine’s courtyard, with one such reserve being uncovered in the 1930’s during an initial excavation of the building’s surrounding wall. These preliminary discoveries provide contemporary archeologists with the hope that more caches may be found, along with additional clues that could provide architects the information needed to restore the building to a state more reflective of its original glory.

The return of archeologists to this excavation site gives us a real time example of how these scientists often come back to previously explored sites in order to answer new questions. This is a commonly weaved thread in any scientific discipline, as researchers must oftentimes repeat experiments with nuanced changes to reflect the importance of newly acquired knowledge. In the case of the Powder Magazine, archeologists are attempting to reverse the effects of not just time, but of human interference, so that both the integrity of the original building and of the history that happened there may remain strong.

A small collection of Powder Magazine artifacts are displayed above including cannon balls (center), musket balls (bottom right), roof tiles (upper right) and a Virginia half penny (upper left) which were only minted for one year before the revolutionary war.

If you’re itching to learn even more, information on more archeological dig sites in the area can be found here.

The Method in the Madness

Unless you are an archeologist yourself, you probably have little knowledge about what the methods to an archeological excavation may entail. In this case, I advise you to abandon everything that you think you learned from Indian Jones at the door. Archeology is methodical, its labor intensive, its data critical, and every single artifact that is discovered is considered valuable, not just the Ark of the Covenant.

First, the archeologists use ground penetrating radar to complete a geophysical survey in order to gain insight into which areas have the greatest potential for discovery. A team then strategically marks the areas to be excavated in predetermined rectangular plots. The team then begins to slowly work, sifting the earth from each distinct soil layer through mesh screens so as not to miss even the smallest artifact.

The age of soil can be predicted by observing the thickness of each horizon and the weathering of the parent material found there. For instance, rocks and minerals which slowly erode to form soil will be found in larger pieces then older and deeper soil layers. After recording the location and the relative soil horizon that each artifact is found in, the artifacts are transported to a laboratory where they can be cleaned, examined, and interpreted using knowledge of the time and clues gathered from other archeological discoveries. This process allows archeologists to piece together what any excavation site may have looked like throughout different depths of its past. Like all sciences, to make way for newly uncovered evidence, these interpretations will remain fluid and open to change.

Historical buildings such as this one have helped bring history to life since the colony’s restoration in 1926. Modern archeological practices are now helping to refine their interpretation and may affect how they reenact that history in the future.

Why is Williamsburg worth Discovering?

I once read a sign posted outside a cemetery which read “Pause a moment as you pass by. As you are now, so once were we. As we are now, so shall you be.” This statement is sobering, and makes me slightly uncomfortable every time I think about it, just as every true piece of poetry should.

I have a tendency to learn about history as if it is not still being created, as if I am reading a story that leads to the inevitable ending which is the moment I live in now. Unless I suffer from undiagnosed narcissism, I do not believe this feeling of egocentrism is unique. It is easy to assume that we live in the most important time period, because to us that is what it is, but consider for a moment that the “current day” is a relative term. One day we too will leave behind relics of our time here that may wait hopefully for the moment they may touch human hands again.

We feel disconnected from our history because it is hard for us to relate to it. We think that because past time periods are different than today, that the people who lived back then must be different than us as well. This is a fallacy, the same one that leads us towards the tendency of fixating on the traits that differentiates us from our neighbors. It is frequently forgotten, but as members of the same human race, we all have a lot more that binds us together than tears us apart. In truth, the colonists of 18th century Williamsburg were people not so different from us, living in a time that is not so different from our own. Perhaps if we began to think of these people as we could only hope our predecessors will one day think of us, we would find greater motivation in telling their stories.

Only 20% of Colonial Williamsburg property has been excavated. Imagine the life stories and the historical events that will re-emerge through the efforts of these excavations.

Thank you for joining us at Discovery Detour, where the destination is always unknown.